“Inside Out” by Keri Blakinger is a partnership between NBC News and The Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering the U.S. criminal justice system. The column draws on Blakinger’s unique perspective as an investigative journalist and formerly incarcerated person.

My favorite TikTok video starts with a clean-cut man in a baseball cap walking down a snowy street.

“I’m going to my favorite teacher’s house from when I did my 21-year prison bid,” he tells the camera. “She is the BOMB. She doesn’t know I’m coming. Here we go, let’s surprise her!”

He knocks, then turns back to the camera.

“I’m So Nervous Right Now,” the caption reads.

Seconds later, the door swings open.

“Mr. Lacey? Oh my God! How are you?” his former teacher cries, dissolving into laughter and then tears before inviting him inside.

The 54-second video went viral last year with more than 2.7 million views. Michael Lacey — who did 21 years in Indiana prisons and now posts under the username Comrade Sinque — went on to become one of the top creators in the niche realm of prison TikTok, where people who did time tell the rest of the world what it’s like and put faces to the concept of mass incarceration.

“People are just giving you a real example about what that life looks like,” he told me. And the community of formerly incarcerated creators and their followers have been overwhelmingly supportive, he said. “It’s kind of ironic,” he added, “but prison TikTok is one of the most positive places on the app.”

There is, of course, another variety of prison TikTok — videos by currently incarcerated people with contraband phones who show the world the abysmal conditions they live in and the variety of terrible food they’re being served. Those kinds of videos began going viral near the beginning of the pandemic. But now, it's former prisoners’ posts that seem to be getting more attention.

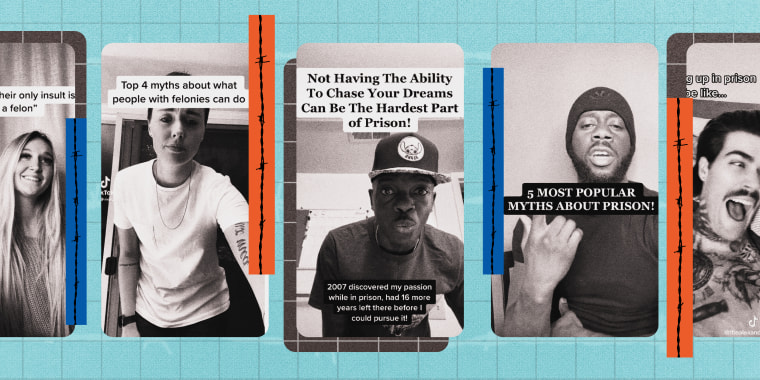

Some of the videos are heartwarming, like Lacey’s. Others are sobering, like Jessica Kent’s posts about giving birth while incarcerated. Some are informative, like Tayler Arrington’s posts about the use of sign language behind bars and how women handle periods in prison. The latter was a 59-second video showing the 24-year-old in her living room staring straight at the camera, spitting out rapid-fire facts. It racked up more than 11 million views.

“When you’re in county jail, they don’t sell tampons — you have to make them yourself,” she says, prompting a host of horrified comments.

Still other videos are funny, like Colin Rea’s riffs on ridiculous assumptions people make about prison. Baked into every viral post is a little bit of a redemption narrative: This is a place where people who did time can become influencers, both earning a living and shaping the way their followers think about prisons and the people inside them.

“People think ‘criminal’ and they immediately think the worst people imaginable,” Rea told me from his home in Pennsylvania. “It’s so much more common than people realize, and there’s such a stigma behind it.”

Like Lacey, he hopes that telling his story to hundreds of thousands of followers could help change that.

More than 1 billion people use the app every month, and there are hundreds of distinct communities from BookTok to LesbianTikTok, from FoodieTok to StripperTok. To find those communities, users swipe up again and again to scroll through a selection of clips curated by the app’s closely guarded algorithm.

After months of lurking and scrolling through videos, I ended up with a personalized feed — known as a For You Page — filled with videos about lesbians, depression and prisons, which will come as exactly no surprise to anyone who knows me. When I started writing this column, I made the jump from scrolling to posting after recording a few quick videos about jailhouse lingo, how gender works in prison and the economics of prison labor.

I quickly realized I am better at words than videos, and called my friend Morgan Godvin for help. Like me, she did time for a charge stemming from her addiction and also forayed into TikTok a few weeks ago. Her very first video — about why she went to prison — went viral overnight.

As we scrolled and chatted, I noticed how hard it was to find creators of color, unless I started scrolling through the other side of prison TikTok, the videos made by current prisoners. A lot of them don’t show their faces because it’s illegal to have a cellphone in prison, but when they do reveal themselves, the demographics are almost the opposite of post-prison TikTok.

When I pointed that out to Morgan, who is white, she spotted it, too.

“Most people that have been to prison are people of color,” she said, “so why are most content creators about prison white?”

Lacey, with 863,000 followers, is Black, but among the most-followed prison accounts he’s more the exception than the rule. A thorough scouring of the app’s lockup-related hashtags turned up a few other Black creators, including fitness trainer Dontrell Britton (322,000 followers) and prison consultant Dejarion Echols (56,000 followers).

“It’s just another example in the digital world of underrepresentation of people of color,” Lacey told me. “I know that there’s people on TikTok that are in the same lane that I am. But when it comes to Black creators, you almost have to go consciously try to find them — they don’t pop up on your For Your Page.”

Casey Fiesler, an assistant professor who studies tech ethics at the University of Colorado Boulder, wasn’t surprised to hear Lacey’s observation. But, she said, it can be hard to pinpoint a single reason so many of the most-followed prison TikTok creators are white.

“There are a ton of confounding factors about who is on TikTok and who is not and even who has been released from prison and who has not,” she said. “But there certainly has been a lot of conversation over the past couple of years about the potential for racism in the TikTok algorithm.”

After all, since the point is to predict which videos users will like, algorithms can reflect the biases of their human users and creators, as well.

In 2020, TikTok cited a “technical glitch” and apologized for suppressing “Black Lives Matter" posts and vowed to promote more diversity on the platform. A representative did not immediately respond to a request for comment on this column.

As Morgan and I kept talking through the ups and downs of the platform, she pondered the benefits of being able to share lived experience behind bars with thousands of followers — and then offered a different suggestion as to why the platform might have fewer Black creators posting about post-prison life.

“There might just be fewer content creators of color because they can’t afford the stigma of being a felon,” she said. “I was able to build a whole professional career on the fact that I have been to prison, and I have to recognize that there is an element of privilege in that.”