Deepsea mining proposal of Vancouver's The Metals Company under scrutiny

"I don't think it's obvious that deepsea mining is a much better way to do it, in terms of the environment." — Oceanographer Craig Smith

Article content

A Vancouver-based mining company has come up with what it considers to be a cleaner option for producing minerals needed to power green transportation.

Instead of blasting minerals out of the earth from terrestrial mines, The Metals Company wants to scoop up some of the billions of tonnes of mineralized rocks that litter vast tracts of the deep Pacific Ocean bottom between Hawaii and Mexico.

The rocks, called polymetallic nodules, formed naturally over millions of years and contain nickel, copper and manganese — minerals essential for making lithium batteries. Their concentrations are so rich that the company refers to them as “a battery in a rock.”

However, as The Metals Company embarks on its biggest exploration project, accompanied by an environmental study, the company has come under scrutiny, including from a New York Times’ investigation that raised questions about its close relationship with the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the UN-sponsored regulatory body that governs activity in the open ocean.

The report shone additional light on environmental concerns about wide-scale disturbance of the deep abyssal plain, some 4,000-to-6,000 metres beneath the surface, one of the most stable, biodiverse and sensitive deepsea environments on the planet.

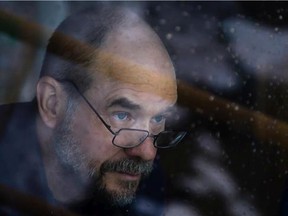

“I don’t think it’s obvious that deepsea mining is a much better way to do it, in terms of the environment,” said oceanographer Craig Smith.

Smith, a professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, has studied the deepsea ecosystems of the Clarion Clipperton Zone, the area being explored for mining, since 1988. Smith says he isn’t opposed to exploiting some of the resource but wants the public to fully understand the environmental consequences of mining.

“One of the other really interesting things about deepsea mining is that there are a lot of unknowns, and once we do it, we can’t go back,” Smith said. “There’s no way to fix this deepsea ecosystem.”

Metals Company officials didn’t respond to Postmedia News requests for an interview by deadline, but in a corporate video CEO Gerard Barron cited the “impactful” potential of its proposal.

“This is about the drive towards net-zero emissions,” Barron said. “Mother Nature needs this enormous resource, and it all sits in one little area called the Clarion Clipperton Zone.” He characterized it as a “fraction of the ocean floor,” with “enough materials we need to build all the electric vehicle batteries, all the storage batteries several times over.”

In August, the company raised US$30 million to take on the next stage of its exploration, a pilot test of its mining technology, along with an environmental monitoring program, which Barron called “a foundational step towards our journey to completing our application for an exploitation permit from the (ISA).”

The company is conducting the work in partnership with its subsidiary, Nauru Ocean Resources Inc., which is working in an ocean zone reserved for the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru. On its website, The Metals Company estimates there would be enough minerals in this zone to build 140 million electric vehicles.

The company hopes to carry its work beyond the July 2023 target date for the International Seabed Authority to adopt exploitation regulations for the industry.

Part of the environmental monitoring program will be to create a framework for an “ecosystem-based (environmental monitoring and mitigation plan)” for commercial operations.

Ultimately, the company wants to extract nodules, refine them into metals for use in batteries and other clean-energy components then see those metals, particularly from batteries, recycled at their end of life in a closed-loop system.

Smith, however, is concerned that the ISA doesn’t have enough resources and is “being overworked” to come up with reasonable exploitation rules or a mining code by that 2023 deadline, which was prompted by the Nauru government’s interest.

“Nauru believes that we have a duty to the international community to carry out this request to bring this certainty for the benefit of all stakeholders,” according to a statement on the government’s website.

The ISA is “doing the best job they can,” Smith said, and has done good things such as setting aside large no-mining areas, considered areas of “significant environmental interest,” before exploitation has even started.

“But they are being asked to do things beyond their capacity,” Smith said.

In its corporate materials, The Metals Company characterizes the 4.5-million-square-kilometre Clarion Clipperton Zone as a “vast underwater desert” that has little food and one of the “lowest biomass levels of any planetary ecosystem.”

Smith, however, said there is still a high level of biodiversity within this zone, with hundreds, perhaps thousands of species of deepsea organisms dependent on the nodules themselves as habitat.

So removing nodules, which form over millions of years around bits of matter such as shells, sharks teeth or sand that sink to the bottom, eliminates that habitat.

Smith added that scientists have little understanding of the long-term impacts from sediment plumes that would be raised by deepsea mining equipment, creating dark conditions in a highly light-sensitive environment for long periods of time.

The long-term impacts of continuous noise from operations expected to go on 24 hours a day for 30 years, Smith said, are also unknown — both at absolutely silent ocean bottom in the abyssal ecosystem and at surface with the operation of mining ships among sea mammals and other marine life.

“I actually think the best way forward to understanding the environmental impacts would be to use what I would call a precautionary approach,” Smith said. “Just possibly license one single mining operation in the CCZ and monitor it very, very well for a decade to see what the impacts are in space and time, then decide: Is it too much even with one mining operation (or) can we scale up?”

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.